For those of us who don’t read Hebrew (and even for those of us who do), the English translations in our prayer books can be a helpful way to understand the text. But what you may not know is that the very first English translation of the High Holiday service was published in colonial times — even before an English language version had been developed in England. Its debut revolutionized American Jewry. And its pioneering translator, Isaac Pinto, is surely one of American Jewry’s unsung heroes: a man whose passions for America and for Judaism helped create the very concept of a Jewish-American identity.

Isaac Pinto, a Sephardic Jew, emigrated to the American Colonies in 1740, when he was 20 years old. Upon arrival, he joined Shearith Israel, the only synagogue in New York City at the time, although his job as a merchant required him to spend most of his time on the road. Pinto immersed himself in the controversial politics of his day, and despite his nomadic lifestyle, found the time to write several articles for publications in New York and South Carolina in support of American patriotism and independence from British taxation. His erudition made him influential in the debate over independence. He became one of the signers of the Non-Importation Act in 1770 (a prelude to the Embargo Act) and later, because he spoke several languages, would become one of the first official translators hired by the United States government.

When Pinto first arrived in the colonies, he was surprised to find the early Jewish communities had little to no familiarity with Hebrew. Recognizing the need for a readable Siddur, Pinto decided to start the painstaking translation process. As he wrote in his preface, “it has been necessary to translate our Prayers, in the Language of the Country wherein it hath pleased the divine Providence to appoint our Lot.”

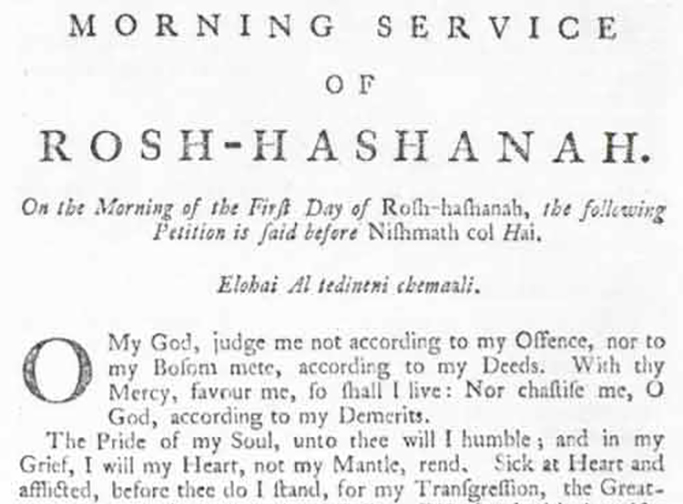

In 1761, he published his “Evening Service of Roshashanah” followed by “Prayers for Shabbath, Rosh-Hashanah and Kippur” in 1766. As opposed to the Siddurim we use today, Pinto decided not to include any Hebrew text at all. These translations became the first Jewish prayer books published in America, and propelled Pinto’s reputation as a notable intellectual and academic. On the cusp of the American Revolution, he corresponded with many leading philosophers and academics, including Rabbi Isaac Karigal of Palestine and President Ezra Stiles of Yale College (who referred to him as “a learned Jew at New York”).

Pinto’s scholarly pursuits were always tied to his deeply-held belief in American sovereignty and self-reliance. He wrote numerous articles on the subject in theNew York Journal, and passionately encouraged a new self-identity for American Jews. He was highly popular in New York’s Jewish society: in 1784, he was asked to be the clerk of Shearith Israel’s congregation but turned it down due to his advanced age of 64. When he died in 1791, his obituary in the New York Journal noted his standing as a linguist, historian and philosopher, and referred to his staunch support of American liberties.

Next time you open a Siddur, take a minute to appreciate the genesis of its English translation — and of your own revolutionary identity as an American Jew.